Knee Anatomy

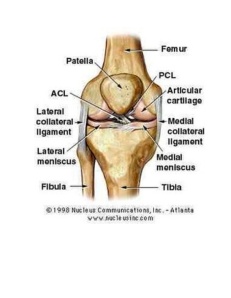

While there are four bones that come together at the knee, only the femur (thigh bone) and the tibia (shin bone) form the joint itself. The head of the fibula (strut bone on the outside of the leg) provides some stability, and the patella (kneecap) helps with joint and muscle function. Movement and weight bearing occur where the ends of the femur called the femoral condyles match up with the top flat surfaces of the tibia (tibial plateaus).

There are two major muscle groups that are balanced and allow movement of the knee joint. When the quadriceps muscles on the front of the thigh contract, the knee extends or straightens. The hamstring muscles on the back of the thigh flex or bend the knee when they contract. The muscles cross the knee joint and are attached to the tibia by tendons. The quadriceps tendon is a little special, in that it contains the patella within it. The patella allows the quadriceps muscle/tendon unit to work more efficiently. This tendon is renamed the patellar tendon in the area below the kneecap to its attachment to the tibia.

Four ligaments, thick bands of tissue that stabilize the joint, maintain the stability of the knee joint. The medial collateral ligament (MCL) and lateral collateral ligament (LCL) are on the sides of the knee and prevent the joint from sliding sideways. The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) form an “X” on the inside of the knee and prevent the knee from sliding back and forth. These limitations on knee movement allow the knee to concentrate the forces of the muscles on flexion and extension.

Inside the knee, there are two shock-absorbing pieces of cartilage called menisci (singular meniscus) that sit on the top surface of the tibia. The menisci allow the femoral condyle to move on the tibia surface without friction, preventing the bones from rubbing on each other. Without the menisci, the friction of bone on bone would cause inflammation, or arthritis.

Bursas surround the knee joint and are fluid-filled sacs that cushion the knee during its range of motion. In the front of the knee, there is a bursa between the skin and the kneecap called the prepatellar bursa and another above the kneecap called the suprapatellar bursa.

Each part of the anatomy needs to function properly for the knee to work. Acute injury or trauma as well as chronic overuse both cause inflammation and its accompanying symptoms of pain, swelling, redness, and warmth.

Types and Causes of Knee Injuries

While direct blows to the knee will occur, the knee is more susceptible to twisting or stretching injuries, taking the joint through a greater range of motion than it can tolerate.

If the knee is stressed from a specific direction, then the ligament trying to hold it in place against that force can tear. Ligament stretching or tears are called sprains. These sprains are graded as first, second, or third degree based upon how much damage has occurred. Grade-one sprains stretch the ligament but don’t tear the fibers; grade-two sprains partially tear the fibers, but the ligament remains intact; and grade-three tears completely disrupt the ligament.

Twisting injuries to the knee put stress on the cartilage or meniscus and can pinch it between the tibia surface and the edges of the femoral condyle, causing tears.

Injuries of the muscles and tendons surrounding the knee are caused by acute hyper flexion or hyperextension of the knee or by overuse. These injuries are called strains. Strains are graded similarly to sprains, with first-degree strains stretching muscle or tendon fibers but not tearing them, second-degree strains partially tearing the muscle tendon unit, and third-degree strains completely tearing it.

There can be inflammation of the bursas (known as bursitis) of the knee that can occur because of direct blows or chronic use and abuse.

Acute knee injuries fall into two groups; those where there is almost immediate swelling in the joint associated with the inability to bend the knee and bear weight, and those in which there is discomfort and perhaps localized pain to one side of the knee, but with minimal swelling and minimal effects on walking.

Knee Injury Treatment

Almost all knee injuries will need more than one visit to the doctor. If no operation is indicated, then RICE (rest, ice, compression, and elevation) with some strengthening exercises and perhaps physical therapy will be needed. Sometimes the decision for surgery is delayed to see if the RICE and physical therapy will be effective. Each injury is unique, and treatment decisions depend on what the expectation for function will be. As an example, a torn ACL (anterior cruciate ligament) would usually require surgery in a young athlete or a construction worker, but the ACL may be treated non-operatively with physical therapy in an 80-year-old who is not very active.

If there is no reason to surgically correct the injury, then opportunity exists to strengthen the quadriceps and hamstring muscles. When a joint like the knee is injured, the muscles around it start to weaken almost immediately. This is also true after a surgery, which can also be considered a further injury. Strong muscles in the pre-operative state allow the potential for easier post-operative therapy.

Muscle Tendon Injuries, MCL and LCL Injuries, ACL and PCL Injuries, and Meniscus Tears

The medial collateral ligament (MCL) is a broad, thick band that runs down the inner part of the knee, from the femur (thighbone) to about four to six inches from the top of the tibia (shinbone). The MCL’s primary function is to prevent the leg from over-extending inward, but it also is part of the mechanism that stabilizes the knee and allows it to rotate. Injuries to the MCL commonly occur as a result of a strong force hitting the outside of the knee that causes the MCL — and, possibly, other ligaments on the inside of the knee, such as the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) — to stretch or tear.

The lateral collateral ligament (LCL) is a thin band that runs along the outside of the knee and connects the thighbone (femur) to the fibula, which is the small bone that runs down the side of the knee and connects to the ankle. Similar to the medial collateral ligament (MCL), the LCL’s primary function is to stabilize the knee as it moves. Tears to the LCL commonly occur as a result of direct blows to the inside of the knee, which can over-stretch the ligaments on the outside of the knee and, in some cases, cause them to tear.

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) runs in a notch at the end of the femur (intercondylar notch) and originates at the back part of the femur (posterior-medial aspect of the lateral femoral condyle) and attaches to the front part of the tibia (tibial eminence). In the knee, the ACL prevents forward movement of the tibia. It also provides roughly 90 percent of stability in the knee joint.

The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) is about two inches long and connects the femur to the tibia at the back of the knee. It limits the backward or posterior motion of the tibia (shinbone). Twisting or overextending the knee can cause the PCL to tear, leaving the knee unstable and potentially unable to support a person’s full body weight. The PCL is the strongest ligament in the knee, and tears often are associated with traumatic injuries rather than sports injuries. PCL tears can happen when the knee is violently forced backward or when the front of the shin is hit hard, for example when the knee strikes the dashboard during a car accident.

In general, almost all of these strains are treated with rest, ice, compression, and elevation (RICE). Ibuprofen or aspirin can be used as an anti-inflammatory medication.

The common cause of injury is either hyperextension, in which the hamstring muscles can be stretched or torn, or hyper-flexion, in which the quadriceps muscle is injured. Uncommonly, with a hyper-flexion injury, the patellar or quadriceps tendon can be damaged and rupture. This injury is characterized by the inability to extend the knee and a defect that can be felt either above or below the patella. Surgery is required to repair this injury.

Except for elite athletes, tears of the hamstring muscle are treated conservatively without an operation, allowing time, exercise, and perhaps physical therapy to return the muscle to normal function.

MCL and LCL Injuries

These ligaments can be stretched or torn when the foot is planted and a sideways force is directed to the knee. This can cause significant pain and difficulty walking as the body tries to protect the knee, but there is usually little swelling within the knee. The treatment for this injury may include a knee immobilizer, a removable Velcro splint that keeps the knee straight and keeps the knee stable. RICE (rest, ice, compression, and elevation) is the mainstay of treatment.

ACL and PCL Injuries

If the foot is planted and there is force applied from the front or back to the knee, then the cruciate ligaments can be damaged. Swelling in the knee occurs within minutes, and attempts at walking are difficult. The definitive diagnosis is difficult in the emergency department because the swelling and pain make it hard to test if the ligament is loose. Long-term treatment may require surgery and significant physical therapy to return good function of the knee joint. Recovery from these injuries is measured in months, not weeks.

Meniscus Tears

The cartilage of the knee can be acutely injured or can gradually tear. Acutely, the injury is of a twisting nature; the cartilage that is attached to and lays flat on the tibia is pinched between the femoral condyle and the tibia plateau. Pain and swelling occur gradually over many hours (as opposed to an ACL tear which swells much more quickly). Sometimes the injury seems trivial and no care is sought, but develops chronic pain over time. There may be intermittent swelling, pain with walking uphill or climbing steps, or giving way of the knee that results in near falls. History and physical examination often can make the diagnosis and MRI may be used to confirm it.

Resources used for this article include: Mayo Clinic, Cleveland Clinic, UC-San Franciso articles and studies.